The Joy of Victory, the Agony of Defeat:

Stereotypes in Newspaper Sports Feature Photographs

Every day, working newspaper photographers have the following problem to solve: how, in a very limited amount of time, to make photographs which illustrate newspaper stories, and will be accepted by editors whose criteria is that readers be able to read and understand the photograph quickly, and that the photograph have sufficient “impact” to catch the readers’ eye and entice them to read the text. Newspaper photographers solve this problem by making highly conventionalized images, using a limited number of visual components and compositional devices to illustrate a limited number of ideas or “stories.” These photographs offer ready-made solutions to the problem: editors accept them, readers know how to read them, subjects know how to pose for them. The photographs that appear in newspapers are, overall and in their details, a result of this conventionalization.

Because of the peculiar character of sports reporting in daily newspapers, sports feature photographs are a particularly good place to study the conventionalization of news imagery. Sports is one area of news which, by tradition, is allowed to be openly partisan and “non-objective.” The local paper, primarily interested in the fortunes and fate of the local teams and their players, wants the management, manager and players of the home team to win games and championships. It rejoices in wins, suffers for losses, praises exemplary behavior, and chastises bad actors (as New York papers criticized and denounced George Steinbrenner for years).[1]

Other areas of the paper are, also by tradition and convention, “objective,” reporting “the news” and “the facts” and avoiding “editorializing” in the news columns. As many analyses (Molotch and Lester 1974, Tuchman 1978, Gans 1980) have shown, however, they are not objective in that way (in fact, there is a good argument that such neutrality is impossible). Because the partisanship in sports is explicit, not a cause for shame or apology, we can see the devices of visual partisanship most clearly there and should be able to use them as clues for the general analysis of partisanship in news photography.

Sports is a good area to study the processes of conventionalization, too, because newspapers carry only a few, highly simplified stories about sports. With the photographs that illustrate them, they present a pared-down, highly selective view of the actual world of sports, stories about a make-believe world in which certain aspects of our society are emphasized and made the basis for the entire description of a world. We can call this world Sportsland. In this simplified world, only a few important things go on, there are only a few issues, only a few commonly held values.

If the sports section of the daily newspaper gives a complete and accurate report of events in a world parallel to ours (as in the science fiction stories of parallel worlds), then we can discover the characteristics of that world from this accurate and complete report. This is the opposite tack to thinking of reporting on sports as incomplete and partial (which, of course, we know to be the case), and taking it allows us to see what sort of world the sports page promotes.

The photographs I used to define Sportsland are entries from the sports feature category of the 46th Annual Pictures of the Year (POY) Contest, judged in March of 1989 at the University of Missouri School of Journalism. Newspaper photographers take the contest very seriously. Winning can help them get a better job or a raise, and the most well-known professionals enter. Each year, over 2000 photographers, working for newspapers of every size, kind of ownership, and geographical area, and for magazines, as well as “unaffiliated” (freelance) photographers, enter. Photographers select their own entries, choosing the pictures they’ve made during the past calendar year that they think best embody professional standards of excellence. The pictures need not have been published to be entered, although most have. The categories for single newspaper photographs include: spot news, general news, feature, sports action, sports feature, pictorial, and portrait/personality. The categories for groups of pictures include news picture story, feature picture story, newspaper portfolio of the year, and magazine portfolio of the year.

The entries constitute an excellent sample for a study of the conventionalization process, one that would be difficult to gather in any other way but that avoids obvious sources of sampling bias. Photographers submit pictures which they think and hope embody the professional values the judges will use in arriving at a decision so, even if the photographs are not representative of the universe of pictures actually made or published, they represent the system of ideas participants in the system aspire to. Photographers no doubt submit their “best,” not their run of the mill, pictures. But that imperfection in the sample works against the hypothesis I will present, and therefore is not a flaw. That is, photographers submit pictures they think have something “special” about them, because of which they will stand out from the run of the mill. If even pictures selected to be different are very similar, as they are, the interpretation offered here will be even more strongly confirmed.

Newspaper Sports Feature is one of the categories for individual images. 1521 photographs made during the calendar year 1988 were entered in this category. The contest entry brochure describes a sports feature photograph as “a sports related feature photograph,” and a feature photograph as one with “human interest, a fresh view of the commonplace.” This differs from the Newspaper Sports Action category, “a peak action photograph that captures the competitive spirit.”

The six judges are professionals, working photographers and editors chosen by the administrators of the contest. Paid only expenses, they still spend as much as two weeks in the judging process, looking at thousands of projected slides. They vote electronically, each judge pushing a red button to reject the slide, green to keep it in the running, on slides projected for only a few seconds, and make their decisions rapidly. Judges can request caption information, but usually don’t until the final round, when the hundreds of entries in a category have been narrowed to ten or so finalists.

What are the characteristics of the world—call it Sportsland—the photographs describe?

The main activities are Big Time Sports, highly organized and publicized games and events—usually professional or quasi-professional college sports—in which winning is a major news item. Who wins the Big Games is important for everyone.

Sportsland is divided into two categories: winners and losers. If you aren’t a winner, you’re a loser. It’s Vince Lombardi Land: winning is not the main thing, it’s the only thing.

Sportsland is also divided into Us and Them: the home team and the visitors. When the world is going right, the home team wins. (The home team can be literally the team from the town the paper is in, or it can be by extension, as in the Olympics, where the U.S. is the home team.)

The people who inhabit SportsLand are the participants in Big Time Sports, the players and athletes. They are in the prime of adult life: young to youngish-middle age; in top physical condition; morally superior in character; hard working and highly skilled; under intense pressure to do their best and to win.

These are the chief characteristics of Sportsland. I’ll describe others in connection with the major categories of the analysis below.

Conventionalized Imagery

The basic elements of the analysis are stories, gestures, and compositional devices.

Stories are the basic plots the photographs illustrate. What kinds of things can happen in the world being pictured? Which one of them has happened here? In a competitive sporting event, the basic stories are winning or losing. One team or person wins, the other loses, as in baseball, basketball, or tennis, or one from a field of competitors wins while the others lose, as in gymnastics or bicycle racing.

Newspaper photographers talk about making pictures that “capture the story telling moment.” “Capture” implies that the photograph already exists objectively. Not constructed, it is, literally, out there for the taking.

Not so with the story. Stories depend on context. If, as a photographer, you are covering a game in which your city’s team is playing “at home,” the story is what happened to your team. Did they win or lose? If your team won, the “story telling picture” tells the story of their win. But the same game will be covered by out-of town photographers, for whom the story of the same event is that their team lost. Their “story telling picture” tells the story of defeat and dejection. Wire service photographers often function as the “out-of-town photographer.” So, at a basketball game, photographers from the local papers plant themselves under the local team’s basket, but the wire service photographer sits at the other end of the court to photograph the visiting team scoring. (This does not occur when a game (e.g., a playoff) has national importance.)

Some sports provide potential negative instances. In golf or tennis, for instance, there are no “home teams.” The same process occurs, however, with “favorites” replacing “home teams.”

Gestures—the movements and postures of the people photographed—are the elementary visual components out of which the pictures are made. Some common gestures in sports photographs involve the position of the head (up or down) and arms, and of the body in relation to the ground (jumping or kneeling), as well as ways of two people relating to each other (hugging or confrontation).

Compositional devices are ways of organizing visual components in the frame so that certain ideas are communicated. The most common compositional device is standard for all catagories of newspaper photographs: one main subject, centered and occupying most of the frame, with the background blurred, through manipulation of the depth of the photographic field, to avoid distracting attention from the subject, thereby creating a shallow pictorial space (this composition is often used in pictures of winners). A photograph composed this way is thought to have maximum impact. A different compositional type uses deep space to provide a sense of isolation, achieved by placing the main figure at the far end of a bench that slants back diagonally, a device frequently used in photographs of “losers.”

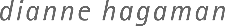

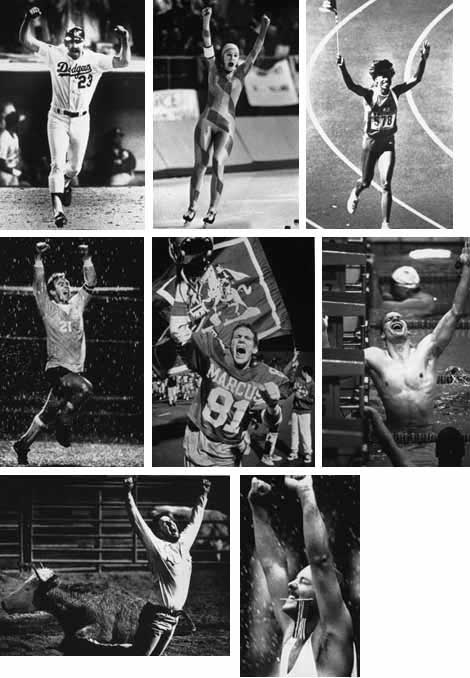

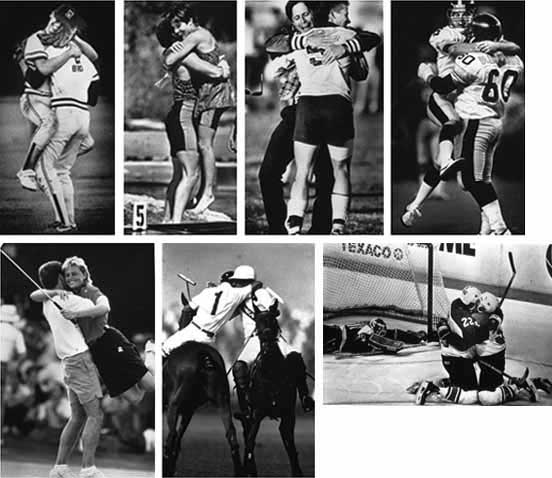

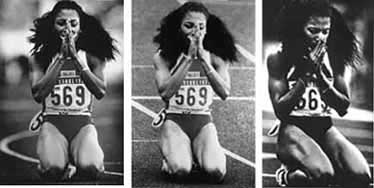

The photographs in Figures 1, 2 and 3 exemplify the most common story: “winning.” 371 of the 1521 photo entries in the sports features category (24.4%) were “winners,” often so labeled by the photographers, stereotypically as “The Joy of Victory.” Titles are useful for the analysis, because they tell you the point of the picture as the photographer intended it. Since the photographers write the titles, they are good clues to what the picture was intended to “mean”: “pain,” “the joy of victory,” “the agony of defeat,” “walking wounded,” “exhaustion,” “ouch,” “out cold,” “flat out.” (Table 1 gives the frequencies for the major categories of the analysis.)

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

The standard set of gestures used to convey the story of winning include: arms and head up, mouth open, hugging, jumping, and running. The gestures are combined in a variety of ways, but the direction of movement is always “up.” (Lakoff and Johnson 1980, 14–17, analyze the metaphoric meanings of “up and “down”). The standard composition for photographs of “winners” is the one referred to above: the subject centered in the frame, filling most of it, and a blurred background. Table 2 gives the frequencies for gestures and compositions within categories (Panel A, for instance, is for winners). Every picture categorized as a winner contains one or more of the above mentioned gestures signifying winners. “Mixed,” the largest subcategory, consists of pictures that have several. The other subcategories, designated by single dominant gestures, usually contain others in a subordinate role.

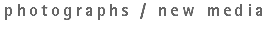

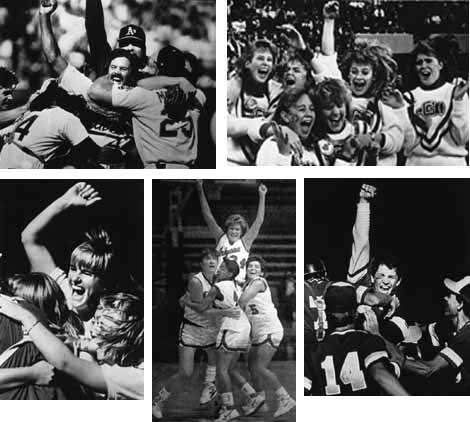

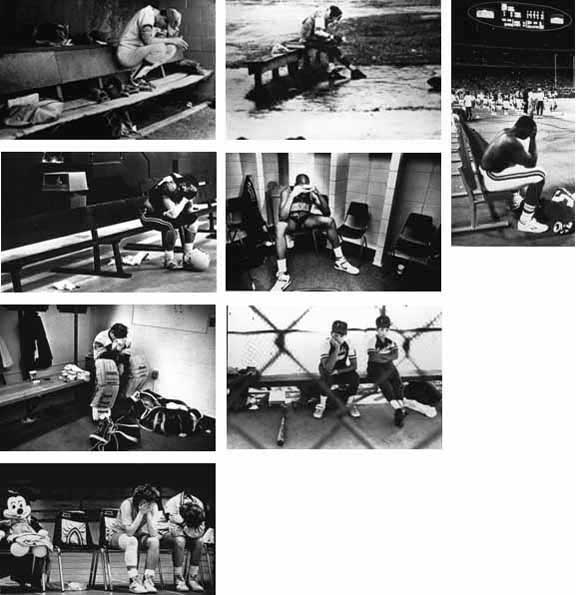

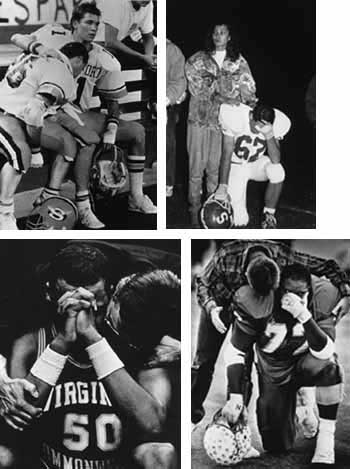

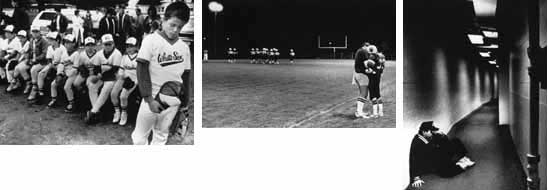

Losers (see the photographs in Figures 4, 5 and 6) feel intense agony. 192 of the 1521 sports feature photographs (12.6%), stereotypically titled “The Agony of Defeat,” pictured losing. The gestures illustrating losing point down: head down, body slumped and often actually on the ground. Some gestures—hugging, for example—appear in pictures of both winning and losing; the gesture’s meaning is determined by how it is combined with other gestures.

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Many photographs of losers are composed like those of winners: a dominant, centered subject with a blurred background. In a frequent variation, however, a wider angle of view is used: the subject is placed, alone, at one end or corner of the frame rather than centered in the middle. A strong diagonal, such as a bench or long hallway, or even a receding line of teammates, extends to the subject from the opposite end of the frame. The combination creates a sense of deep, lonely space surrounding the dejected loser. (see Figures 4 and 7 and Table 2, Panel B) These photographs are often made with wide-angle lenses (35mm and wider) which have the optical characteristic of making objects from foreground to background appear to be farther apart, and of greater relative size (e.g. foreground objects appear larger relative to background objects) than they appear to the human eye.[2]

Figure 7

Winners are often photographed in groups, celebrating “the joy of victory,” but “the agony of defeat” is usually pictured alone; occasionally one other person consoles the loser. Photographers and editors consider photographs that include winners and losers in the same frame (Figure 8) as especially good.

Figure 8

Sportsland is a dangerous place and athletes, giving their all for the team and for victory, can come to grief through injury. An injured player may be an object of pity at the moment of the injury, but will eventually be banished from Sportland as incapable of playing the part. The ultimate injury, one which ends a career through death or permanent disability, is a story about the ultimate loss.

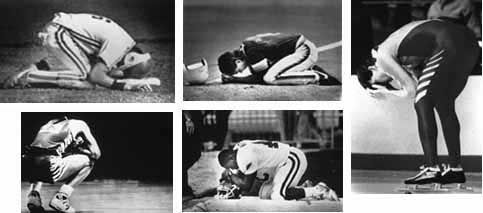

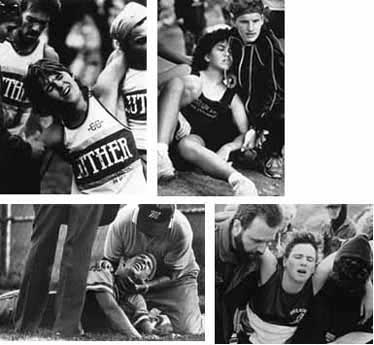

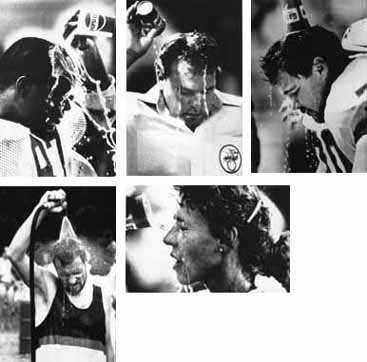

Another conventional story, rooted in this view, describes athletes as embodying the admirable character traits such a life requires (111 entries, 7.3%, Table 2, Panel E). They are fearless and brave, willing to undergo extreme physical trials; their endurance in the face of, and acceptance of the character-building aspects of, punishment and torture display their willingness to sacrifice for the team, or for the sport itself. Photographs of an injured player, just hurt and lying bravely on the ground (”Oh, the pain of it!” and “The agony”), illustrate determination, and the amount of pain, injury and defeat players must suffer as heros (Figure 9). Other people are compassionate; they send for help and, while it’s coming, are helpful and consoling: “There when you need them.” Another conventionalization of the theme of pain and determination centers on water: tightly framed pictures of overheated and exhausted athletes pouring water on their heads and squirting water into their mouths (Figure 10). Physical discipline and suffering—”going the last mile”—are equated with strength of character. In fact, winning and losing are themselves equated with character: losers don’t hustle, don’t give their best.

Figure 9

Figure 10

Still another story (30 entries) emphasizes the admirable character of athletes by idealizing the team and the group character of the sports effort. The players cooperate in an ideal fashion to win. Their moral superiority consists in part in being selfless and putting the good of the team ahead of their own personal good. (This part of the story of Sportsland has come under a good deal of pressure as the big money aspects of the world have increased in importance.) When We win it is, exactly, a team win. We see players building a pyramid of hands as an illustration of solidarity and the sacrifice of individual glory for the good of the team (Figure 11). These pictures are a source of common metaphors which permeate business and other organizations, stories about sacrificing for the good of the team, and the moral value of being a team player.

Figure 11

In non-team sports, an idealized apotheosis of the sport takes the place of the team. When someone breaks a record in track (e.g., the four minute mile), it is a victory for the entire sport, in its collective battle against nature.

The rest of the world appears in Sportsland in supporting roles. The chief supporting role is that of fan, the people who buy the tickets and attend sporting events. Fans admire and look up to athletes. Their recognition of athletes’ special virtues is one of the rewards of winning. A special case of the fan is the reporter (in such guises as television announcer and even as photographer) who also admires and looks up to the athlete. 117 entries (7.7%, Table 2, Panel C) illustrated these stories. Fans root for the team, and are jubilant or dejected, like the players, when it wins or loses. News photographers find the clowning and gimmicks fans engage in to show support of their team or make fun of the opposing team worth making pictures of. A favorite fan “antic” is to wear something incongruous on your head: a mask of a favorite player, a watermelon carved like a football helmet, paper bags. Typical photographs in this type show two or more fans, for instance, wearing pumpkins on their heads, tightly framed with an out-of-focus background (Figure 12).

Figure 12

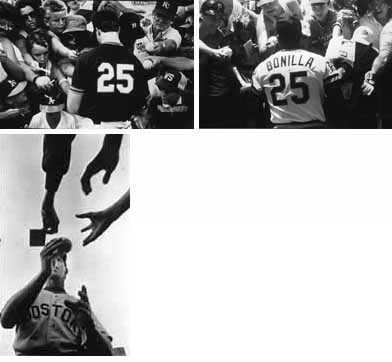

Fans also strive for some connection with the players, and many pictures, with titles like “We Won,” show them venerating their idols. The photographer’s problem here—to make a composition that shows fan support and adulation—is solved by making a photograph in which eager fans surround the athlete. A common compositional device has the athletes centered in the frame, surrounded by fans whose outstretched arms proffer autograph books or baseballs (Figure 13). A variation of this composition, in which the media embody the admiration of the athlete, shows the star surrounded by a circle of microphones (Figure 14).

Figure 13

Figure 14

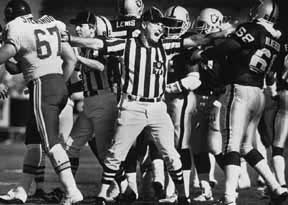

Officials (97 entries or 6.4%, Table 2, Panel D) appear in sports feature photographs as either provoking or, alternatively, managing the passionate emotions attached to winning or losing. They provoke these emotions by making “close calls”; when they call one against Us, our team and our coach attack the official. When emotions rise between players and teams, the officials step in to keep the peace, something like police (Figure 15). Officials are not personalities in their own right like coaches or athletes. They stand for rules and structure. Some photographs in the confrontation/complaining sub-category use the compositional device of an out of focus official in the foreground (a blurred, impersonal symbol recognizable by the striped jersey, for example) and a sharply focused complaining athlete or coach in the background (Figure 16).

Figure 15

Figure 16

Coaches (27 entries, Table 2, Panel F) are almost always recognizeable because they often wear suits and ties, and/or because they are often of an inappropriate size (too small) or age (too old). They assist the team in its efforts to win—sometimes, like a father (the majority of coaches in Sportsland are male), comforting, cajoling, inspiring, chastising—and represent it in relations with officials (protesting “unfair calls”), the media, and the public.

Many sports feature pictures (260 entries, 17.1%, Table 2, Panel G) intend to be humorous. Though humor is not itself a “story,” certain conventional “funny pictures” are part of the photographic repertoire. Standard funny pictures include people with contorted faces, grimacing, sticking their tongues out; footballs and basketballs that appear to be someone’s head; people in awkward or unusual postures, e.g., people photographed in midair, upside down or seeming to fly. Rear ends are sure-fire laughs (except, of course, when they belong to women in bathing suits).

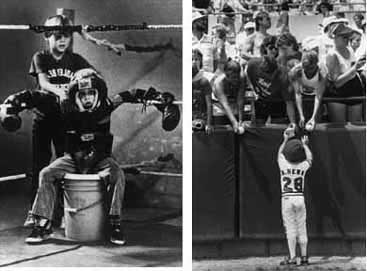

People who do not fit the criteria of age and health cannot be serious players in Sportsland. An elderly person cannot be a serious competitor; “real athletes” are younger, capable of “real” sports efforts and victories (Figure 17). Young children cannot be serious players. This is why photographs of children engaging in the same gestures and activities as full-fledged participants (e.g., hanging your head in despair after losing, or signing autographs, as in Figure 18) can only be ironic or comic.

Figure 17

Figure 18

In “Fathers and Sons,” a sentimental version of such photographs (24 entries, Table 1), little boys emulate the “big boys,” real athletes: the little ice hockey player, all suited up and holding his stick, photographed from the sidelines as he watches the real athletes play (”Maybe One Day,” Figure 19). The cuteness of these photographs embodies assumptions about the values of sport, how children learn from adults, how good it is for them to follow in these particular footsteps. (When children are shown watching adults do something “bad,” like drink or shoot drugs, the picture is thought to convey a strong social message.) The name of this category is not literal, but generic of a type: 18 of the photographs show a male athlete with a small boy and have titles like “Daddy’s Boy,” “Walking with Dad,” and “Like Father, Like Son.” Two of the photographs in this category show females. In one a female runner hugs a little girl, and in the other a male runner kisses a little girl.

Figure 19

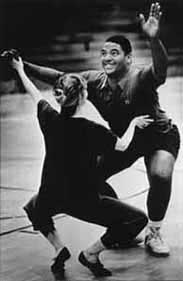

These photographs draw attention to the difference . They “work” because viewers know the stereotype. In fact, photographers make and select the photograph on the assumption that viewers know the stereotype, know what a “real” athlete is. The photograph, far from questioning the stereotype, reinforces it. An image of women doing things more “appropriate” for a man (and vice versa: a big football player learning modern dance as in Figure 20) can be used humorously, though this isn’t always true: women body builders may look incongruous but it doesn’t seem funny.

Figure 20

A similar device, not intended as humorous, appears in the 17 entries of physically or mentally disabled athletes. The point of these pictures is that, even though these people have a disability, they’re doing sports. The titles are revealing: a tightly framed photograph of a man with one leg holding a golf club is titled simply “One Legged Golfer.” A small man standing alone on the ice, holding hockey sticks and a face mask, is titled “Dwarf Manager” (Figure 21). Other photographs of disabled athletes would normally be seen as action photographs (pictures of athletes while they’re actually participating in the sport: running the race, throwing the pass, lifting the weight) (Figure 22). What makes these “features” is that the disabled athletes are defined primarily by their disability, their playing is incidental to their disability. Like the humorous pictures of children, their difference from the stereotype makes the photographer see the image as a feature picture. It’s the right activity, but the wrong person: this is not real sports action and these are not real athletes. Their ability to play at all becomes the story; it doesn’t matter who wins or loses. It’s like Samuel Johnson’s remark about a report of a woman preaching: “Sir, a woman’s preaching is like a dog walking on his hinder legs. It is not done well; but you are surprised to find it done at all.” (Boswell 1980. See also Hughes 1971.)

Figure 21

Figure 22

I classified 55 photographs (3.6%) as “other.” Some of these images illustrate topics that appeared only once or twice and did not fit neatly into the major categories just discussed (for example, figures 23 and 25, which are discussed below, were placed in this category). Some others were not classifiable because it was not clear, without the context of the written story they illustrated, what they were about. Not every photographer has succeeded in making a photograph that “reads,” either on first glance or on more detailed inspection, as being about anything in particular. No one prevents the entry of these unsuccessful photographs in the contest, and it should not be necessary to be able to classify them all. (Not being a successful newspaper photograph does not mean the photograph is “bad.” One, discussed below, is an excellent photograph, from the point of view of social investigation.)

Two kinds of pictures entered in sports features do not fit into any of the categories so far mentioned and are irrelevant to this analysis. These pictures belong to the newspaper genres “pictorial” and “portrait” rather than sports and use the conventions of these other genres. I discuss them to make clear what they are.

I classified 136 entries (9%) as “pictorial.” These pictures are often described as “beautiful” or “interesting.” They rely for their interest on such graphic elements as color, blurs, shadows, pattern, and unusual angles. Characteristically, they either have no discernible story, or the story is almost completely subordinated to graphic devices and to mood. Such pictures may appear anywhere in the paper, not just the sports section, and their makers simply take advantage of a sports setting to find the appropriate patterns. They are for the most part as conventionalized as the pictures I have been considering, but the conventions are those of the pictorial image, not those of the sports story. Similarly, the 53 photographs (3.5%) I classified as “portraits” rely on the conventionalized forms available for newspaper portraits, and are “sports features” because the people in them are sports celebrities. Both “Pictorial” and “Portrait/Personality” are, in fact, other categories in the POY contest. Pictorial is defined in the contest rules as “a beautiful, graphic image: composition, tonal and color qualities are more important than subject matter.” A Portrait/Personality is “a picture of a person that reveals the essence of the subject’s character.”

If you take winning, losing, character and team as being versions of the same overall story of competition, and officials and coaches as subsidiary players in that drama, then 828 of the 1521, or 54%, deal with this stereotypical story in the canonical forms I’ve discussed. If we remove pictorial photographs and portraits from the denominator of the fraction, the proportion rises to 62%.

The important conclusion is that the these sports feature pictures are overwhelmingly alike, similar in the story being illustrated, the gestures chosen to illustrate the story, and the compositions used to organize them in the frame.

Similar images: the conditions of news photographic work

What is the significance of so many similar images? Photographers have countless choices. Each image could have been made in many different ways. What is at work to produce such simple, repetitive statements?

Given the organization, contraints and conditions of newspaper work, there are good reasons for these photographs to look the way they do. Sports feature photographs, like all newspaper photographs, are made in an organization that includes editors, photographers, readers, and subjects (in this case, athletes). This organization constrains the way photographers work. Editors give them three or four assignments a day covering many different subjects, so that they have very little time to complete an assignment. Typically, they do not have beats, and thus cannot build up an intimate knowledge of any area of activity. As a result, the story is defined for them by the writer who originated the story and filled out a “photo request,” and by the editor who makes the assigment.

Stories are conceptualized and known before the photographer goes to make the photograph. In a standard text for photojournalism students, Angus McDougall, describing the proper way for an editor to make an assignment, simply assumes the prior conceptualization of the story: “Writers and editors requesting photographs should provide necessary background information by attaching story printouts, notes or ideas, realizing that while they are intimate with the story, this will be the photographer’s first exposure to it” (McDougall, 1990, 295). One heading to be filled out by the person requesting the photograph is Story Idea: it “should tell photographers what the story is about, not how to shoot the photograph. Of course, suggestions are always welcome.” Editors know what the story is and photographers, before they leave the office, know too. Their photograph must illustrate that story.

Photographers from different local papers or the wire services are often covering the same story and therefore competing with each other. Every experienced person (which is to say every well-socialized professional) knows what the photo to get is in each situation. Learning to discern what “the picture” is is the equivalent of developing a “news sense,” knowing what “the story” is for an event, what goes in the lead paragraph (Rosenblum, 1978). For example, say “the feature picture” of this particular game is of the victorious coach being carried by the team. But which photographer gets the best picture of the coach being carried? That depends on which picture shows the faces of the coach and players most visible and in sharpest focus, and which picture has the most dramatic facial expressions. If one picture has something distracting in the background, or an awkward composition, then it is given a lower grade.

When editors and colleagues compare photographs of the same event, as they usually can when rival papers print their stories, they criticize photographers who haven’t gotten the “best picture,” the one that best illustrates the preconceptualized story. An editor might say, stereotypically, “This picture doesn’t say ‘losing’ to me. Do you have one that says ‘losing’?” Those who don’t come back with “the picture” that says what it should, when other photographers do, get a reputation of being “inconsistent,” “undependable,” or having “poor news judgment.” Editors will be reluctant to send them on important assignments. Photographers who do get the same picture learn that they have good news judgment.

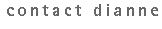

The three pictures of Olympic runner Florence Joiner in Figure 23 were made by three different photographers. All three photographers knew what “the picture” of this particular event was. They not only made startlingly similar photographs (the photographs vary mainly by which photographer was to the left of the others), but chose their photograph as a good example of a years work and entered it in POY.

Figure 23

Working under such constraints, newspaper photographers do not use the camera to investigate events, but instead make photographs from a repertoire of already known images that illustrate already known stories. They compete to make the best version of one of these already known “ideal photographs,” what we can call canonical photographs. Within the requirements of the whole newsgathering system, this is a very efficient way of working. They do not, on the other hand, try to find out something new, nor to test a theory or idea, perhaps modifying it, or describing it visually. Instead, they look for a new way to say the same thing. Photography is not used to investigate and find out about the issue, but rather to communicate a reductive summary of it quickly.

Getting the Picture

The chief skill of the photographer becomes getting the “right” picture, the one the editor will recognize as satisfying the requirements of impact and readability, under such circumstances. Making the images assigned by editors may be routinized, but it isn’t easy. It requires anticipating when and where the combination of elements necessary for the”right” picture is likely to happen and maneuvering yourself into a position to get a “good” photograph of it when it does happen. Once a photographer learns these skills they come to “feel” right physically: standing in the “right place” to make the standard picture feels comfortable, standing anywhere else feels awkward and wrong.

What, specifically, do photographers do to get “the picture”? Specifically, how do you make the generic picture of the isolated, dejected loser? How, given that people are seldom actually alone, even in moments of defeat, do you make an image in which it appears that they are?

First, you remember that image as a picture in your repertoire, one that you know is a “good one” for telling the story of defeat. When it’s apparent that your team is losing, for instance, you look for people sitting away from others with their heads down, or for people coming to console someone sitting in that posture. Once you see the potential, you sense that the generic picture may happen. An important skill is being able to sense when people will move away for a moment, leaving your “subject” momentarily in the generic isolated position. You keep looking for a “clean” background, one whose components won’t interfere with the sense of isolation, If you can’t find it where you are standing, you move until the background has nothing distracting in it. If there are a lot of people behind the athlete, for instance, and none behind you, you run to the other side to get the background with no one in it.

You can frame so tightly—the player on the ground filling the frame—that no one else is visible though, in fact, the player is surrounded by people. The picture is made so that the player’s emotion is all it signifies, giving a straightforward, uncomplicated meaning to the picture. The photograph becomes an ideogram for “dejection” or “loss.” Or you can use a long focal length lens which, when adjusted for a short depth of field or used at a fairly close distance, will isolate a subject, making any background an out-of-focus blur. An editor will say, of any of these pictures, “This says losing.”

Similarly, experienced sports photographers know that, when “your team” is losing, you can always shoot the team on the bench, looking up to see the instant replay on the screen above the scoreboard. Because you already know what happened, you know how they will respond, and can therefore position yourself to get them expressing frustration or disappointment. Sidelines are always a good place to make a feature picture, because you know that is where people will be responding to players leaving the field, and you can get a good “reaction” picture.

In other words, you have a stock of already composed pictures in your head, which you know will illustrate the “story” you’ve decided the game tells. When the story changes, as it often does in sports, you change the nature of your photographing. You might spend the first half of a football game your team is losing, making “good pictures” of defeat and dejection. But then, in the second half, the team comes alive and finally wins, and you go ahead and get good stuff on that. You don’t even bother to look at the film from the first half, because you know it will be useless. (You might look at it for POY, though, because the immediate occasion of the jubilation or dejection will have become irrelevant.)

To know what the story may be, you must know the relevant things that can happen. If a player has had a good day, fans will wait as the player heads for the locker room, leaning over the railing with autograph books. So a generic fan picture can be made there any time the photographer needs it. It belongs in the experienced practitioner’s catalogue of “pictures you can count on,” pictures that can always be made when the appropriate situation occurs.

There are further complications. Every play in a game—baseball is a good example— is the intersection of many stories, and thus can generate many such canonical photographs. The story of, for instance, this pitcher’s earned run average: if the next batter gets a hit, what does that do to his statistics? And what does that mean for his career as that unfolds from play to play and game to game and season to season? And what does it do to the batter’s statistics? The same relevancies arise, of course, for all the other players on both teams.

Some Anomalies

Remember that the contest rules define a feature picture as one that offers a “fresh view of the commonplace.” In practice, the “fresh view” means making a better version of a standard picture, and the taken-for-granted “normal” world, Sportsland, constitutes “the commonplace.” Slight deviations from what “everyone knows” are what are worthy of a photograph.

Every year “good” versions of these standard types of pictures—pictures in which the standard compositions are competently executed—are entered in the POY contest. But to win, as inspection of the winners from successive years shows, the photograph must have a “twist,” a second element that produces a clever or unexpected variation on a standard type.

For example, a conventional type shows animals or birds on a playing field: geese on the golf course during a tournament, a gopher on the baseball field during a game. One award winner shows a goose at a race track, squawking at a trainer passing by on horseback; the “twist” is that the trainer is squawking back (Figure 24). A human response to an animal’s trespass was enough of a “twist,” a fresh “angle,” on a standard sports feature picture to get an award.

Figure 24

Similarly, none of the standard fan pictures described earlier—fans with pumpkins or watermelons carved to look like helmets on their heads, or fans wearing masks of favorite athletes or other celebrities—entered in the 46th annual POY won an award, but the following year, a winning photograph shows teammates and fans of Kareem Abdul-Jabbar facing the camera, holding cardboard masks of Abdul-Jabbar in front of their faces. The “twist” is that Abdul-Jabbar himself is standing in the foreground, his back to the camera.

A number of pictures in the sample seem not to “fit.” Some will fit, with a little forcing: the national anthem pictures, for instance, can be seen as emphasizing the moral character of the athletes. But, in the end, there will be some pictures that just don’t fit the analysis. This is no great matter, because there is no reason to have to explain every picture as being part of the great picture of the absolute conventionalization and stereotyping of the journalistic photograph. These are, after all, pictures the photographers thought would win, and some of them will be examples of misjudgment on their part. Some of them, for instance, just don’t make it: whatever they were supposed to be about isn’t clear, yet they aren’t complex.

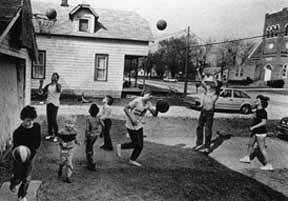

An occasional image is complex, too complex to be a “good sports page” picture, yet maybe good enough to be thought about the way we think about art photographs. There are very few in this sample like that. One example of a photograph that departs in style and theme from the bulk of the sports features entries is Figure 25. This photograph does not have a dominant center of interest isolated from the surroundings, rather, a number of things go on simultaneously in the frame. Information about the neighborhood in which the activity is happening and the possible social class of the players is part of the picture. The activity is not obviously part of an organized, contest sport, and there are no facial or bodily expressions signifying strong emotion. This combination increases the time it takes to “read” the photograph (there’s more going on to look at and make sense of) and decreases the drama. In a system that values the photograph that’s a “good, quick read” and has “strong impact,” it’s no surprise that there aren’t many photographs like this in the sample. The newspaper system itself discourages making alternatives to the standard pictures. In a similar way, the POY judging process discourages photographers from entering alternatives: they don’t win. The standard procedure of viewing hundreds of slides projected only a few seconds apart means that photographs that take longer to “read” stand little chance of winning.

Figure 25

Conclusion

Newspaper sports feature photographs are highly conventionalized and stereotyped images made by photographers using a limited visual vocabulary to tell a limited number of “stories.” These methods result in photographs that look the same even though different photographers, photographing different sports, working for different news organizations in different regions of the country, have produced them.

These photographs are preconceptualized, that is, they embody ideas about the nature of sports developed prior to experience in the situation being photographed. The limited visual vocabulary used severely constrains the the kinds of ideas and relationships the photographs can communicate. The requirement to “shoot tight” for impact and “readibility,” for example, creates an emphasis on a single emotion or idea. Stepping back to include more in the frame would make it possible to establish more complex relationships and ideas within the image. The virtuosity of newspaper photographers consists in their ability to make a better version of a photograph from the standard reportoire of already known images. In so doing, they forego the use of photography as a visual medium to explore and find out about the social world (Ivins 1953).

Newspaper photographers make photographs well suited to the requirements of the cooperative network of people who produce the newspaper, the work organization in which they are embedded. If they don’t do their part as they are supposed to, the flow of work is interrrupted and the system ceases to function efficiently (Becker, 1982). I have talked mostly about photographers, but the newspaper system also includes the people who pose for the photographs and the people who read the newspaper. For readers who are sports fans, the stereotyped image of the local team winning may be meaningful in the way a picture of your own wedding is not “just another” wedding photograph or the child’s picture you carry in your wallet is not “just another” school portrait. Athletes, similarly, may be influenced by the way they see other athletes behave in newspaper photographs, and so behave in similar ways. I have not studied these phenomena, but they would repay careful investigation.

Sports features is only one kind of newspaper photograph, although its extreme stereotyping makes it an ideal category in which to see the relation between a work organization and the characteristic images produced in and for it. But the same organizational constraints–too little time and, instead of photography beats, assignments originated by writers and editors, and the way photographs are expected to function in the newspaper (eyecatching and immediately understood), exist in every category of newspaper photograph. This analysis of newspaper sports feature photographs therefore probably also applies to such other categories as spot news, general news, and feature photographs. The stories told in such photographs and the visual vocabulary used to tell them need to be defined, and the values embodied in these other images need to be scrutinized.

References

Becker, Howard S. 1982. Art Worlds. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Boswell, James. 1980. Life of Johnson. Oxford University Press

Gans, Herbert J. 1980. Deciding What’s News. New York: Vintage

Hughes, Everett C. 1971. The Sociological Eye. New York: Aldine-Atherton.

Ivins, Jr., William M. 1953. Prints and Visual Communication. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Logan, John R. and Harvey L. Molotch. 1987. Urban Fortunes: The Political Economy of Place. Berkeley: University of California Press.

McDougall, Angus (in association with Veita Jo Hampton). 1990. Picture Editing and Layout: a guide to better visual communication. Columbia, Missouri: VISCOM Press.

Molotch, Harvey and Marilyn Lester. 1974. “News as Purposive Behavior: On the Strategic Use of Routine Events, Accidents, and Scandals,” American Sociological Review 39 (February): 101–12.

________. 1975. “Accidental News: The Great Oil Spill as Local Occurrence and National Event,” American Journal of Sociology 1975 (September): 235–60.

Rosenblum, Barbara. 1978. Photographers at Work. New York: Holmes and Meiers.

Tuchman, Gaye. 1972. “Objectivity as Strategic Ritual,” American Journal of Sociology 77 (January): 660–80.